Vienna in year 1900 embodies what Marshall Berman calls the modern environment where men and women are offered promises of adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of oneself and the world and, at the same time, confronted with threats of destruction of everything one has, everything one knows and everything one is.[1] The Gründerzeit (promoter-years) in the later nineteenth century in Austria was a period of intensive industrialization, rapid social expansion and financial speculation. As the capital of the Austro-Hungary Empire, Vienna attracted citizens from far-flung, sometimes hostile provinces united in an uneasy alliance under the crown of the Habsburgs. The population of the capital increased from under half a million in the 1850s to over two million by 1910 during the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph, with less than half of its inhabitants born there. Demographic growth was matched by great technological and scientific advances with the erection of the first electric lights on the Kohlmarkt (1893), the advent of the tram (1894), the vaulting of the river Wien and the regulation of the Danube Canal (1898), the construction of the city’s metropolitan railway network, and the first international automobile race held in Vienna in 1899.[2] Achievements made in fields of medicine and natural sciences began to produce a real effect upon wider circles of the population. The well-known Austrian writer, Stefan Zweig, has described the Viennese’s belief in inexorable ‘progress’ as having the force of a religion.[3] Security, peace, and prosperity of the ruling classes and the power of the Habsburgs were reflected in the Imperial Jubilee celebrations of 1898 This marked the fiftieth anniversary of Franz Joseph’s accession to the throne, an ageless figure himself who played a crucial role in creating an illusion of permanence. Within twenty years, the Dual Monarchy of Austro-Hungary Empire was split into many parts and Vienna reduced to the role of capital of merely the Republic of Austria.

Despite outward appearances, Viennese inhabitants shared a sense of approaching disaster, with the city laden with social issues following the stock exchange crash of 1873 and the Viennese World Fair of the same year that ended as a grandiose financial fiasco.[4] More broadly, there was a surge in suicides, an extraordinary growth in the number of esoteric cults, the emergence of diametrically opposed movements as Zionism and German Nationalism. All this underlined the illusory nature of the balls, marches and parade in the city of the waltz. It was also the time when the Christian Socialist Party began to ascend, culminating in the triumph of mayor Karl Lueger who made political anti-Semitism socially acceptable in Vienna. Death was a dominant motif in the city – the assassination in 1898 of the Empress Elisabeth, wife of Franz Joseph, the untimely deaths of his brother, son, sister-in-law, and heir registered in the collective memory of the Viennese, ultimately setting off World War I when the Archduke Francis Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were killed in 1914. To the psychological novelist and playwright Arthur Schnitzler, living in Vienna felt like being ‘surrounded by an intimation of the end of their world.’[5]

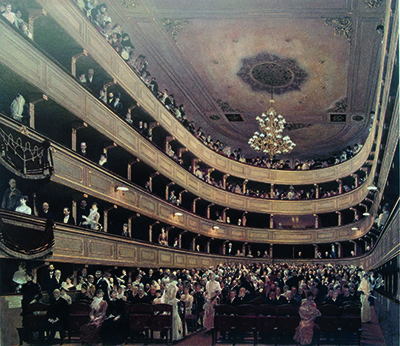

The façade that hid the dark side of Vienna was embodied in the Ringstrasse, a three-kilometer horseshoe-shaped boulevard surrounding Vienna’s inner city constructed in the 1860s as a monument to the Empire. Private mansions housing aristocrats and middle-class households and public buildings such as the Parliament were built in styles mimicking those of the glorious ages, ironically not in real stucco but in cement moulded to imitate the classical, Gothic and Renaissance.[6] Intellectuals, artists and writers growing up in those years developed a hatred for all that was pretentious and false. The architect Adolf Loos (1870-1933) called Vienna a ‘Potemkin city,’ a sham, pretending to be something it was not.

One of the things that the intellectuals, artists and writers found most striking among all that was false was the sexual hypocrisy prevalent in Viennese society. While an epidemic of prostitution under police surveillance in well-defined areas of the city was evident, women were brought up in sterilized environments with every outing chaperoned.[7] Men and women refused to observe Victorian moral codes preached to them while pretending to do so. This was an area where we do see the coming together of ‘progress’ and the underbelly of society, and in many ways, what made Vienna extraordinary. In the area of science and research, serious attention was given to human sexuality by thinkers such as Richard Krafft-Ebing (Psychopathia sexualis, published 1886), Otto Weininger (Sex and character, 1903), Sigmund Freud (Studien über Hysterie (Studies in Hysteria), 1895 and Die Traumdeutung (The Interpretation of Dreams), 1900). Radical writers such as Frank Wedekind, Robert Musil and Arthur Schnitzler introduced sexual problems into their plays and novels. These thinkers probed the inner psyche of the individual, human behavior and the unconscious orientations of our selves in a changing modern era.

It was in this city of Vienna, within a ‘maelstrom of perpetual disintegration and renewal, of struggle and contradiction, of ambiguity and anguish’ that Gustave Klimt and Egon Schiele created their art.[8] Experiencing the crises of modernity in early twentieth century Austria, both artists sought for the truth by unmasking the veil of hypocrisy and going beyond the superficial. The will to truth culminates in fantasies that manifest in their artworks expressed in unique artistic language and style.

[1] Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity (London, New York: Verso, 1983), 15.

[2] Peter Vergo, Art in Vienna, 1898-1918: Klimt, Kokoschka, Schiele and their Contemporaries (London: Phaidon, 1975), 9.

[4] Joachim Ridel, ‘The City without Qualities,’ in Klimt, Schiele, Moser, Kokoschka: Vienna 1900, ed. Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm (Hampshire: Lund Humphries Pub Ltd, 2005), 25-33, at 28.