Art, Migration & Representation Mapping Ethnic Minority Migration and Exhibitions in Hong Kong, 1933–2020

Author's Statement

Hong Kong is a product of human movement. It is a city built, cultivated and developed by migrants and it continues to rest on their labor. This project looks at Hong Kong art through the lens of migration. Exhibition history is presented in parallel with the history of Indian sailors, Gurkhas, African businessmen, Vietnamese refugees, Southeast Asian migrant workers and other non-Chinese Hong Kongers in the city. The result is a juxtaposition that shows the impermeability of Hong Kong art to its non-Chinese communities of color and provokes dialogue about the invisibility of ethnic minorities from the Global South in the making of Hong Kong culture. The causes of this absence lie in discourses on ethnicity, privilege, labor and mobility. Decisive factors include colonial privileges that benefited Euro-American Caucasian communities, restricted access to education, employment and community support for non-Cantonese-speakers, migration policies imposed on migrant workers, asylum seekers and refugees, as well as the elitism of Hong Kong’s art world.[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] These have all played a part in the invisibility of minorities in Hong Kong culture, not merely as artists, but as curators, researchers, scholars, critics and collectors. This project centralizes communities that have been written in the margins to encourage us to reflect on the barriers that have placed them there, whether those barriers exist in our institutions, through our policies or within our own collective ideologies. It is a recognition that minority art histories are Hong Kong art history and our understanding of Hong Kong art and Hong Kong would not be complete without them.

Kam-Yee Law and Kim-Ming Lee, “The myth of multiculturalism in ‘Asia’s world city’: incomprehensive policies for ethnic minorities in Hong Kong,” Journal of Asian Public Policy, 5:1 (2012): 120-125;128-130, doi: 10.1080/17516234.2012.662353.

Kelvin Chi-Kin Cheung and Kee-Lee Chou, “Child Poverty Among Hong Kong Ethnic Minorities,” Social Indicators Research 137, no. 1 (2018): 95.

Michael Ramsden and Luke Marsh, “The ‘right to Work’ of Refugees in Hong Kong: MA v Director of Immigration,” International Journal of Refugee Law 25, no. 3 (2013): 574.

Immigration Ordinance, Hong Kong, Section 13 (1981), https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap115?xpid=ID_1438402608535_003.

Immigration Ordinance, Hong Kong, Section 2(4)(a)(vi) (1997), https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap115?xpid=ID_1438402608535_003.

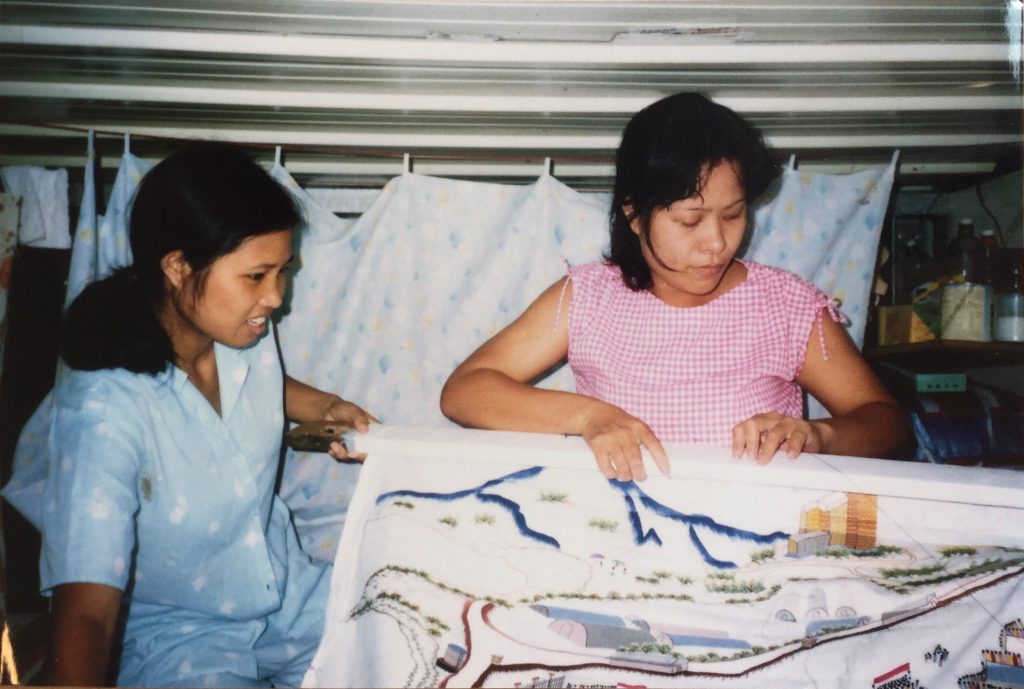

Between 1933 and 2020, there were eight non-profit local exhibitions on ethnic minorities of color: Still Lives: Art by Vietnamese Boat People in Hong Kong (1990), Being Minorities — Contemporary Asian Art (1997), C.A.R.E.: Local Vietnamese Community Art Re-encountered (2008), Afterwork (2016), A Collective Present (2017), Beyond Myself (2018), We Are Like Air (2018) and Nàng Tự Do: The Archive of “Art In the Camps” (2020). While Being Minorities was curated as a reflection on the further displacement of ethnic minorities during the Handover in 1997, the remaining seven exhibitions were either about Vietnamese refugees or foreign domestic workers.[6]

Still Lives, C.A.R.E. and Nàng Tự Do were exhibitions of the same body of work created by Vietnamese refugees under the Art in the Camps program organized by Garden Streams — Hong Kong Fellowship of Christian Artists, which ran from 1988 to 1991 at Whitehead Detention Camp.[7] This enduring reemergence of the art by Vietnamese refugees at Whitehead suggests the city’s particular interest in this specific history and minority community but it could also reflect its tendency to forget them so quickly that it constantly needs their reiteration. Exhibitions about Art in the Camps are concentrated within one or two years before disappearing into invisibility until it reemerges yet again as a topic of interest in the next decade, effectively making Vietnamese refugee art history in Hong Kong circular and lacking in stable development due to its constant repetition.

Being Minorities — Contemporary Asian Art Invitation (Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1997) accessed 4 May 2020, https://aaa.org.hk/archive/2182.

Sophia Suk-Mun Law, The Invisible Citizens of Hong Kong: Art and Stories of Vietnamese Boatpeople (The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2014), xiv-xv.

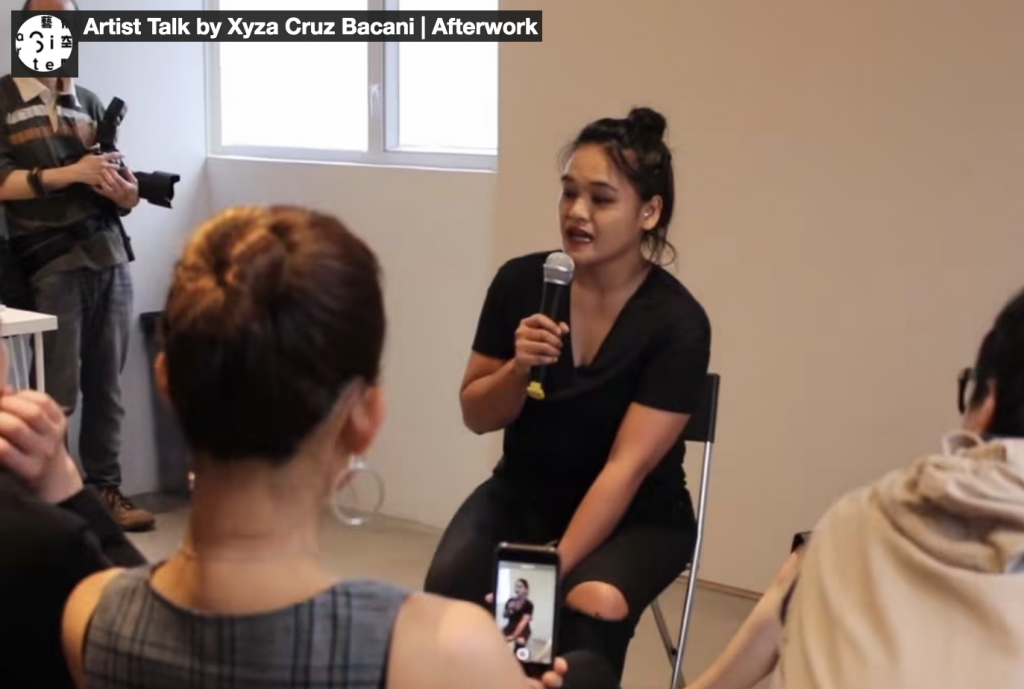

The interest and research in foreign domestic workers, however, has a different trajectory. Exhibitions focused on domestic workers have steadily grown since the 2010s. One could identify Para Site’s major group exhibition, Afterwork, as the landmark show which increased interest in the domestic migrant community. It sought to explore “issues of class, race, labor and migration in Hong Kong, its surrounding region and beyond” by showing artists whose work has been a part of, related to or driven by migrant labor.[8] Yet, as ground-breaking as the exhibition was, it only showed one Hong Kong ethnic minority artist of color, the Filipino-born photographer Xyza Cruz Bacani, among thirty artists and art collectives exhibited. Bacani’s singularity as an artist representing her own community in an exhibition of Afterwork’s scale illustrates the scarcity of minority makers in Hong Kong and further attests to the art world’s impermeability to certain communities.

Para Site, “Afterwork,” accessed 4 May 2021, https://www.para-site.art/exhibitions/afterwork/.

The circularity and repetition of minority histories shown in exhibitions, the lack of minority makers and the bewildered response to Bacani’s success point towards a system unsure of how to include minorities into its canon. Exhibitions like Afterwork, though their motivations and effects are largely positive, exemplify how the ethnic minority is recognized as art’s subject but not its maker. We are embodied by the ceramic bottles of shampoo in Joyce Lung’s Susan (2016), the pixelated videotapes in Elvis Yip Kin Bon’s If You Miss Home (2016), the toy grenades in Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s Hong Kong Intervention (2009), but we cannot be the gears that push the field forward.[12] Our representation rests on the shoulders of one in seven million artists like Bacani, with which we should be content.

I was the only Filipino-Hong Konger Art History graduate in my class and I am now the only Filipino-Hong Konger in my museum’s Curatorial Department. While one person alone could initiate ripples, she cannot make waves. Without ethnic minority presence across the sector, both as artists and as decision-makers within our institutions, Hong Kong art will remain exclusionary regardless of how many exhibitions about us are shown. It will stay impermeable not only to ethnic minorities of color but to most at the socio-economic margins who cannot attain the field’s prerequisites of higher education and a network of influential people. This project is a reminder that we are all migrants to this city and we should all have a voice in its culture and history, regardless of where we come from and where we go next.

Xyza Cruz Bacani (artist), interview with the author, 22 November 2020, transcript, [location in website].

Ibid.

Ibid.

Para Site, “Afterwork,” https://www.para-site.art/exhibitions/afterwork/.

A Collective Present. Spring Workshop, 2017. [Exhibition]

Beyond Myself. Goldsmiths, University of London, 2018. [Exhibition]

Being Minorities — Contemporary Asian Art Invitation. Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1997. Accessed 4 May 2020, https://aaa.org.hk/archive/2182.

Cheung, Kelvin Chi-Kin and Chou, Kee-Lee. “Child Poverty Among Hong Kong Ethnic Minorities.” Social Indicators Research 137, no. 1 (2018): 93-112.

Choi, Susanne Y. P., and Eric Fong. Migration in Post-Colonial Hong Kong. Taylor and Francis, 2017. https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=4980457.

Chou, Freya, Cosmin Costinas, Inti Guerrero, and Qinyi Lim. Afterwork. Para Site, 2016. [Exhibition]

Erni, John Nguyet, and Lisa Yuk-ming Leung. Understanding South Asian Minorities in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press, 2014. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt14jxs35.

Ho, Oscar. Being Minorities — Contemporary Asian Art. Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1997. [Exhibition]

Kam-Yee Law & Kim-Ming Lee. “The myth of multiculturalism in ‘Asia’s world city’: incomprehensive policies for ethnic minorities in Hong Kong.” Journal of Asian Public Policy, 5:1 (2012): 117-134, DOI: 10.1080/17516234.2012.662353

Law, Sophia Suk-Mun. The Invisible Citizens of Hong Kong: Art and Stories of Vietnamese Boatpeople. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2014.

Lee, Melissa Karman. We Are Like Air. Hong Kong Arts Centre, 2018. [Exhibition]

Liang, Yeewoo Evelyna. C.A.R.E.: Local Vietnamese Community Art Re-encountered. Lingnan University, 2008. [Exhibition]

Mathews, Gordon. “Asylum Seekers as Symbols of Hong Kong’s Non-Chineseness.” China Perspectives, no. 3 (114) (2018): 51-58. Accessed August 8, 2020. doi:10.2307/26531931.

Nàng Tự Do: The Archive of “Art In the Camps. Department of Fine Arts, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2020. [Exhibition]

O’Connor, Paul. Islam in Hong Kong: Muslims and Everyday Life in China’s World City. Hong Kong University Press, 2012. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1xwd8h.

Para Site. “Afterwork.” Accessed 4 May 2021. https://www.para-site.art/exhibitions/afterwork/.

Ramsden, Michael and Marsh, Luke. “The ‘right to Work’ of Refugees in Hong Kong: MA v Director of Immigration.” International Journal of Refugee Law 25, no. 3 (2013): 574-96.

Still Lives: Art by Vietnamese Boat People in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Arts Centre, 1990. [Exhibition]

Xyza Cruz Bacani (artist), interview with the author, 22 November 2020. Transcript, [location in site].

About the author

Born in the Philippines, Nicole graduated with a Bachelor of Art History from The University of Hong Kong (HKU) in 2020. Her undergraduate research focused on pre-modern European art, but she is at present most interested in researching themes related to Hong Kong art, Southeast Asian art and migration. She is currently the Curatorial Intern of Visual Arts at M+, Hong Kong’s museum of visual culture, where she is leading their ethnic minority research project.