Mobility, Movement & Spaces Mapping Choi Yan Chi, Ellen Pau and May Fung in Hong Kong’s Art Circle

Author's Statement

By spatially mapping the movement and mobility of three women artists in Hong Kong during specific periods of their career, my timeline foregrounds the artists’ agency in shaping their artistic identity through building art spaces. Against a linear temporal approach to art history, the spatial mapping provokes considerations on how physical and conceptual space influenced art in Hong Kong. Choi Yan Chi (蔡仞姿 b.1949), Ellen Pau (鮑藹倫 b.1961) and May Fung (馮美華 b.1952) are well-established artists who worked in different capacities within and beyond the local art circle. The three artists are selected because they are institution builders who created spaces to make and display art, forming a foundation for the art community that connected artists within and across generations. As founders of cultural organisations, the artists exercised greater autonomy over the display and hence the production of their works. In this way, institutions acted as anchors for the artists to move around the art circle and existed as extensions of their artistic identities that correspond to the artists’ oeuvre.

The three artists studied in this project are leaders with their own visions for Hong Kong art which they realised through their art practice and the institutions they established.[1] As pioneers, these artists had to take on multiple roles to complete the art ecology.[2] Recognising the need for an infrastructure to support and sustain art-making, the artists created art institutions with visions that echoed their own artistic paths. For instance, Videotage’s international focus and its organisation of the Microwave International New Media Arts Festival reflects Ellen Pau’s artistic positioning as an international artist.[3] It also hosts VMAC, the first archive of multimedia works in Hong Kong, aligning with Ellen Pau’s concern over the lack of documentation of art in Hong Kong.[4] The experimental vision of 1a space runs parallel with Choi Yan Chi’s avant-garde spirit which can be understood through her “cross-media experimentations” meant as a means for her to “grow beyond (her) “frames” of creation”.[5] Spaces of Art & Culture Outreach (ACO), including a bookstore and rooftop garden, attests to its mission to “encourage alternative reading” and “advocate green living”, embodying May Fung’s advocations.[6] In an interview in 1998, Fung proclaimed the importance of extensive reading to her learning process as a self-taught artist.[7] Ecological concern is a recurring theme in May Fung’s works, including her Eco-Psycho series of which Sweet Life (2000-2002, fig. 1) is part of. The series draws parallels between the decaying state of the ecology and the psychological state of humans.[8] These examples suggest institutions as extensions of the presented personas of the artists and, in reverse, can be understood as spaces for the artists to structure their public identity.

In their interviews or writings, the three artists acknowledge either explicitly or implicitly their role as a pioneer. Choi Yan-chi, “Am I Turning Right?,” 30–31. Choi recognised herself as a “forerunner of installation art in Hong Kong”; Lee, Christie. “In Hong Kong, What is Home?”In an interview, Ellen Pau recalls that she was one of only eight video artists in Hong Kong when she co-founded Videotage;

May Fung, “From 1989 to Now: May Fung on Video Art” (Edited transcript of talk, Exhibition Five Artists: Sites Encountered at the M+ Museum, West Kowloon Cultural District, Hong Kong, September 19, 2019). https://stories.mplus.org.hk/en/blog/from-1989-to-now-may-fung-on-video-art/.

May Fung describes when Hartmut Jahn, a German artist, came to the Goethe Institut Hong Kong in 1989, he “treated (video artists like May Fung and Ellen Pau) as pioneers of video art in Hong Kong”.

Ellen Pau, “Interview with Ellen Pau, 15 September 1998 (Part 2).”

Videotage organised the Microwave from 1996 – 2006, before it became an independent organisation; Ellen Pau, “Ellen Pau in Conversation with Phoebe Wong,” by Phoebe Wong, Ocula Magazine online, January 18, 2019. https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/ellen-pau/. Ellen Pau mentions reconsidering her relationship with the contemporary art scene in Hong Kong after her solo exhibition at Para Site; In Ellen Pau, “Interview with Ellen Pau, 15 September 1998 (Part 2),” she brought up Canada, Germany, the United States etc. as comparison to Hong Kong’s art scene, suggesting the need to emulate the cultural infrastructures overseas.

Ellen Pau, “Ellen Pau in Conversation with Phoebe Wong.”

Choi Yan-chi, “Am I Turning Right?,” 28–29.

“ACO Team,” Art & Culture Outreach, accessed October 29, 2020, https://www.aco.hk/team. May Fung introduces herself as the ACO Dolphin who “Loves nature, but then cannot forsake art and culture and social responsibility, thus living demi-human and demi-beast between the city and the countryside.”

May Fung, “Interview with Fung Meiwah May, 23 October 1998 — Transcript (English).”

May Fung, “May Fung’s Installation Art: Reflection,” in May Fung: Everything Starts from Here, ed. Leung Chi Wo and Leung Chin Fung, (Hong Kong: Para/Site Art Space, 2002), 22–23, https://issuu.com/parasite_hk/docs/2002_ex_8_box_5_3, Issuu.

Fig. 1 Installation view of May Fung, Sweet Life, 2000–2002, mini LCD monitors and other materials (sheep skins, trees, a children’s toilet, a perspex cubicle with one side covered by a venetian blind, UV light tubes), in May Fung: Everything Starts from Here, 24–25.

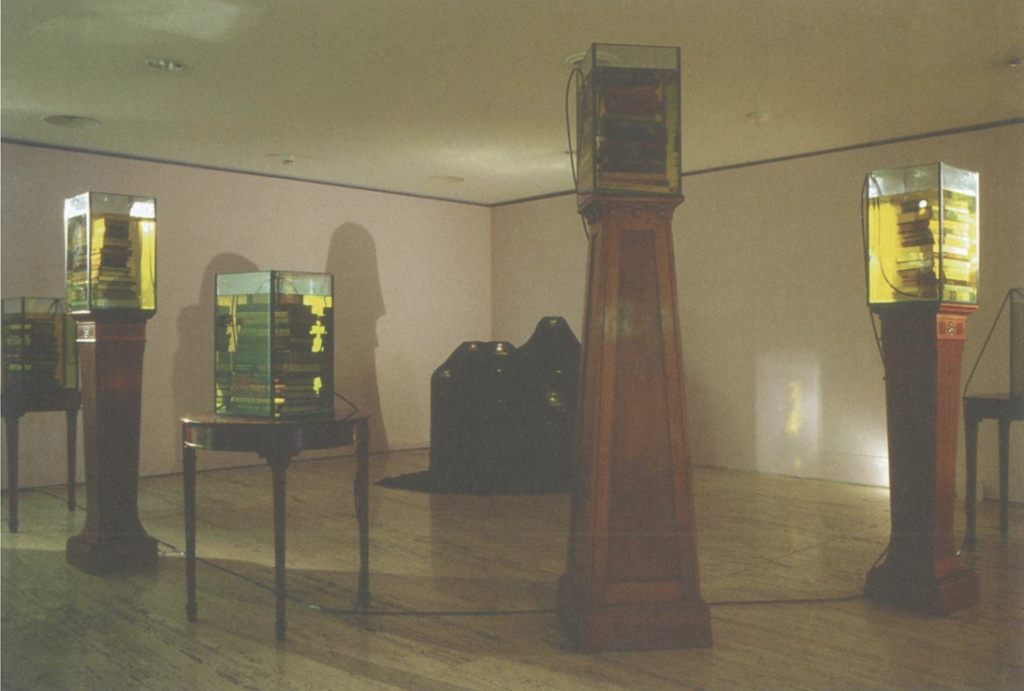

A spatial mapping of the way artists traversed the art circle is particularly important for Hong Kong, where high property prices directly impacted the conditions of art making, physically and thus, conceptually.[9] The gathering and subsequent eviction of artists from the short-lived Oil Street Artist Village of 1998 is marked out in my timeline to emphasise the instability of having a physical space for artists to create, display and communicate about art.[10] The congestion of physical space extended to artists’ anxiety over their conceptual space for art making, corresponding to changes in the social environment and political regime during the late 80s and 90s. This anxiety is encapsulated in Choi Yan Chi’s Drowned III: Swimming in the Dark (1993, fig. 2), part of a series that responded to the “trauma” of the June-Fourth incident in 1984 and the Handover in 1997.[11] Tidily stacked books were contained in glass cases, drowned in oil to slowly disintegrate. These glass cases were put on pedestals that inferred their importance, amplifying the eerie atmosphere and the sense of helplessness as the words in the books were rendered non-functional and disappeared before the embedded ideas could be read. At the time, the medium of installation art connoted an instability which echoed the ephemerality of space in a city with limited land and uncertain sovereignty.[12]

May Fung, “Art Should Not Be Sensible: In Conversation with May Fung,” by Karen Cheung and Chelsea Ma, Asia Art Archive, August 3, 2020, accessed October 29, 2020. https://aaa.org.hk/en/ideas/ideas/art-should-not-be-sensible-in-conversation-with-may-fung. In the recent interview, May Fung described the lack of money and space to be the main challenges faced by emerging artists, forming the motivation behind Arts and Culture Outreach (ACO).

Oil Street Archive, Asia Art Archive. https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/oil-street-archive.

The “Save Oil Street” campaign launched by tenants of the Oil Street premise speak to the opposition of artists against giving up their physical space for creation.

Choi Yan-chi, “Am I Turning Right?,” 24–25.

Choi Yan-chi, “Am I Turning Right?,” 28–31. Choi recalls that mediums of performance and installation art were ways to defy stable identities and existing frameworks in art; Lo Kwai-cheung, “Installing Instability” in [Re]Fabrication: Choi Yan-chi’s 30 years, Paths of Inter-disciplinarity in Art, ed. Linda C. H. Lai. (Hong Kong: Para/Site Art Space, 2006), 112–115, https://www.para-site.art/publications/refabrication-choi-yan-chis-30-years-paths-of-inter-disciplinarity-in-art/, Issuu. Choi’s contemporary Lo Kwai-cheung (羅貴祥) describes understanding her work as avante-garde and links between “the will to transgress the confinement of space as a container” and “the subversive impulses within an orderly paradigm” in installation art which “subtly refers to the character of our contemporary society.”

Fig. 2 Installation view of Choi Yan Chi, Drowned III: Swimming in the Dark, 1993, in The First Asia Pacific Triennial, Queensland Art Gallery, Australia, in [Re]Fabrication: Choi Yan-chi’s 30 years, Paths of Inter-disciplinarity in Art, ed. Linda C. H. Lai. (Hong Kong: Para/Site Art Space, 2006), 83. https://www.para-site.art/publications/refabrication-choi-yan-chis-30-years-paths-of-inter-disciplinarity-in-art/.

Against the theme of disappearance and instability, the people activating art spaces sustained their communities even as institutions and spaces are destabilized. The formation of Videotage in 1986 by Ellen Pau, May Fung, Wong Chifai (黃志輝) and Comyn Mo (毛文羽), who met through the then-disbanded Phoenix Cine Club, reflects a continuity overlooked in institutional histories. Relational links between artists and art institutions also provide interesting ways to think about the ideological links between the art practices of different artists. Geographical proximity between Videotage and Zuni Icosahedron, a performance art group, shaped both the works of May Fung and Ellen Pau.[13] May Fung’s Thought 3 (1989) includes a video documentation of Zuni’s theatre performance October, using the theatre stage as a metaphor for life.[14] Ellen Pau’s Love in the Time of Cholera (1989) includes clips documented from the same performance by Zuni.[15] A rhizomatic mapping of Hong Kong’s art circle can reveal connections that would be neglected in a linear narrative of Hong Kong art history.

Christie Lee, “In Hong Kong, What is Home? Ellen Pau Tackles the Question In Her 30-Year Retrospective,” Zolima Citymag, January 1, 2019, https://zolimacitymag.com/hong-kong-home-ellen-pau-tackles-the-question-in-her-30-year-retrospective/. From its inception Videotage shared space in Happy Valley with Zuni Icosahedron, an experimental performance art group, before moving into the Oil Street Artist Village in 1998; May Fung, “Interview with Fung Meiwah May, 23 October 1998 — Transcript (English).” May Fung mentions that her participation in Zuni’s performances heightened her awareness of body movement and performativity; Ellen Pau’s works such as Love in the Time of Cholera (1989) and Drained II (1989) uses video documentations of Zuni’s performances. “Ellen Pau: What about Home Affairs? — A Retrospective,” 17 names the late 1980s as a “milestone era when the artist (Ellen Pau) began to experiment with screen-based media in combination with stage, dance and installation arts”.

Lok Fung, “From Personal to Political: Deconstructing May Fung’s Short Film and Video Creations,” In May Fung: Everything Starts from Here, ed. Leung Chi Wo and Leung Chin Fung. (Hong Kong: Para/Site Art Space, 2002), 8–9. https://issuu.com/parasite_hk/docs/2002_ex_8_box_5_3, Issuu; May Fung, “Interview with Fung Meiwah May, 23 October 1998 — Transcript (English).” May Fung talks about Thought 3 (1989) as a work that mixes the medium of video screening and solo reading, an element of theatre.

E-catalogue for “The Great Movement: Ellen Pau Solo Exhibition,” Edouard Malingue Gallery online, published 2019, unpaginated. https://edouardmalingue.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Ellen-Pau_E-catalogue.pdf.

Beyond local connections, long distance networks reflected in my timeline reveal moments of increased external interest in Hong Kong art following the June-Fourth incident in 1984 and the Handover in 1997. These networks provided artists in the late 80s and 90s with the foundation to consider Hong Kong’s position as a cosmopolitan city and challenge the East/West narrative to reading Hong Kong art.[16] Writing about her Drowned series, Choi Yan Chi notes and compares the different responses based on the cultural context the work was staged.[17] Her training and experience outside Hong Kong supplemented her with an in-depth perspective of the reception to her work in different contexts, an awareness that impacted the way she considered her position in the field.[18] This global awareness not only shaped the artists’ personal art making practices, but also the way they assessed Hong Kong’s cultural sphere and the institutions they founded to contribute to Hong Kong’s art ecology.

Carolyn Cartier, “Hong Kong and the Production of Art in the Post/Colonial City,” China Information 22, no. 2 (2008): 248–252. Cartier proposes locality as a way of digressing from the China/West narrative in Hong Kong art, using a point of view of Hong Kong as a liminal space.

Choi Yan-chi, “Am I Turning Right?,” 26–27. Choi makes comparison between the responses of “Chinese, Asians and Germans” who associate Drowned with the “destructiveness of totalitarianism” and the “British, Australians, Canadians as well as New Age intellectuals” who felt “a sense of relief”.

Ibid., 26–27. Choi Yan Chi has a BFA and MFA from The Chicago Institute of Art and resided in Canada from 1993 – 1997. She writes about an anecdote from her Fellowship show in 1976 that can be read as a turning point in from her practice in painting to installation. Her tutor’s response to her painted works made her feel an “otherness” that turned her away from her conviction of her role to “steer Chinese contemporary art” through painting, which instigated Choi’s exploration of “new domains” as she returned to Hong Kong.

For the three artists I traced in my timeline, institution-building is significant in two-folds: it established the particular artists as leaders, while laying a foundation for the local art ecology. Institution-building was also a way for the artists to claim physical and conceptual space, acting as anchors for the artists as their roles shifted throughout their artistic careers, and reflecting the artistic concerns of its founders which coalesced with the reputation of the institution. By foregrounding the artists behind institutions and visualizing the mobility of the three artists, my timeline prompts investigation into how an artist became an artist in Hong Kong and emphasizes the artists’ agency through institution-building which granted them additional cultural capital and autonomy to shape their artistic identity.

“ACO Team.” Art & Culture Outreach. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.aco.hk/team.

Cartier, Carolyn. “Hong Kong and the Production of Art in the Post/Colonial City.” China Information 22, no. 2 (2008): 245–275.

Cheung, Ysabelle. “The Life of an Image.” Artomity Magazine, December 30, 2019. https://artomity.art/2019/12/30/ellen-pau/.

Choi, Yan-chi. “Am I Turning Right?” In [Re]Fabrication: Choi Yan-chi’s 30 years, Paths of Inter-disciplinarity in Art, edited by Linda C. H. Lai, 14–33. Hong Kong: Para/Site Art Space, 2006. https://www.para-site.art/publications/refabrication-choi-yan-chis-30-years-paths-of-inter-disciplinarity-in-art/. Issuu.

Choi, Yan-chi. From ‘Oil Street’ to ‘Cattle Depot’. Hong Kong: 1a Space, 2001.

Chow, Vivienne. “’We Can’t Afford Another Generation Too Lazy to Think’, Says Arts Adviser.” South China Morning Post, January 20, 2014. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1409172/we-cant-afford-another-generation-too-lazy-think-says-arts-adviser.

DeWolf, Christopher. “At site of Hong Kong’s first Artists’ Village, Art has come Full Circle – The Story of Oil Street, North Point, and How it Earned its Name.” South China Morning Post, March 1, 2020. https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/travel-leisure/article/3048327/site-hong-kongs-first-artists-village-art-has-come-full.

E-catalogue for “The Great Movement: Ellen Pau Solo Exhibition.” Edouard Malingue Gallery online. Published 2019. https://edouardmalingue.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Ellen-Pau_E-catalogue.pdf.

Exhibition brochure for “Ellen Pau: What about Home Affairs? — A Retrospective.” Para Site online. Accessed October 5, 2020. https://www.para-site.art/exhibitions/ellen-pau-what-about-home-affairs-a-retrospective/.

Fung, Lok. “From Personal to Political: Deconstructing May Fung’s Short Film and Video Creations.” In May Fung: Everything Starts from Here, edited by Leung Chi Wo and Leung Chin Fung, 2–15. Hong Kong: Para/Site Art Space, 2002. https://issuu.com/parasite_hk/docs/2002_ex_8_box_5_3. Issuu.

Fung, May. “Art Should Not Be Sensible: In Conversation with May Fung.” By Karen Cheung and Chelsea Ma. Asia Art Archive. August 3, 2020. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://aaa.org.hk/en/ideas/ideas/art-should-not-be-sensible-in-conversation-with-may-fung.

Fung, May. “From 1989 to Now: May Fung on Video Art.” Edited transcript of talk for the exhibition Five Artists: Sites Encountered, M+ Museum, West Kowloon Cultural District, Hong Kong, September, 2019.

Fung, May. “Interview with Fung Meiwah May, 23 October 1998 — Transcript (English).” By Leung Chiwo Warren. Asia Art Archive. October 23, 1998. https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/library/interview-with-fung-meiwah-may-23-october-1998-transcript-english.

Fung, May. “May Fung’s Installation Art: Reflection.” In May Fung: Everything Starts from Here, edited by Leung Chi Wo and Leung Chin Fung, 22–23. Hong Kong: Para/Site Art Space, 2002. https://issuu.com/parasite_hk/docs/2002_ex_8_box_5_3. Issuu.

Lai, Linda Chiu-han. “Contemporary “Women’s Art in Hong Kong” Reframed: Performative Research on the Potentialities of Women Art Makers.” Positions 28:1 (February 2020): 237-74. Accessed October 4, 2020. doi: 10.1215/10679847-7913132.

Lee, Christie. “In Hong Kong, What is Home? Ellen Pau Tackles the Question In Her 30-Year Retrospective.” Zolima Citymay, January 1, 2019. https://zolimacitymag.com/hong-kong-home-ellen-pau-tackles-the-question-in-her-30-year-retrospective/.

Lee, Christie. “Local Art: Like its Namesake Bus Line, 1a Space is Quintessentially Hong Kong.” Zolima Citymag, January 18, 2018. https://zolimacitymag.com/artist-choi-yan-chi-turned-1a-space-into-quintessential-hong-kong-gallery/

Lo, Kwai-cheung. “Installing Instability.” In [Re]Fabrication: Choi Yan-chi’s 30 years, Paths of Inter-disciplinarity in Art, edited by Linda C. H. Lai, 110–115. Hong Kong: Para/Site Art Space, 2006. https://www.para-site.art/publications/refabrication-choi-yan-chis-30-years-paths-of-inter-disciplinarity-in-art/. Issuu.

“May Fung.” Hysan95. Accessed 5 Oct, 2020. http://www.hysan95.com/interview/may-fung/.

Oil Street Archive. Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong. https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/oil-street-archive.

Pau, Ellen. “Ellen Pau in Conversation with Phoebe Wong.” By Phoebe Wong. Ocula Magazine online. January 18, 2019. https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/ellen-pau/.

Pau, Ellen. “Interview with Ellen Pau, 15 September 1998 (Part 1).” By Leung Chiwo Warren. Asia Art Archive (September 1998). WAV, 1:32:19.

https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/library/interview-with-ellen-pau-15-september-1998-part-1.

Pau, Ellen. “Interview with Ellen Pau, 15 September 1998 (Part 2).” By Leung Chiwo Warren. Asia Art Archive. WAV, 13:20, September 15, 1998. https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/library/interview-with-ellen-pau-15-september-1998-part-2.

PAU, Ellen. Individual File: Ellen PAU. Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong.

“She Said Why Me, 1989.” Video Media Art Collection. Videotage. Accessed 5 October, 2020. http://vmac.org.hk/web/details.php?tag=1651&page=2.

Tyrell, Clare. “May Fung.” South China Morning Post, 2002. https://www.scmp.com/article/396905/may-fung.

About the author

Yi Ting is a recent graduate and teaching assistant at the University of Hong Kong (HKU). She was very fortunate for the opportunity to lead the Hong Kong Art Timeline project during the summer of 2020 with Nicole Martin Nepomuceno. She finds modern Indian art fascinating, and has won the regional prize for the Global Undergraduate Awards in the Art History category for her paper on Abanindranath Tagore. At the moment, she is preparing to pursue her MA in Art History at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, focusing on Chinese painting from the late Ming to Qing period.