Interview with Byron Kim

2 July 2018

New York

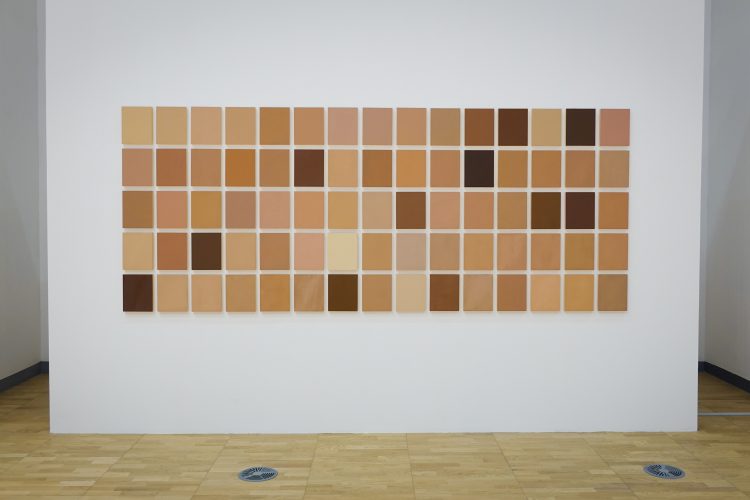

How was the experience of exhibiting Synecdoche at the 1993 Whitney Biennale?

Originally Synecdoche came into being in the early 90s—possibly even in the late 80s. When a friend of mine was visiting from Canada, and I simply painted, the color of skin on his forehead. It was during a time when I was just beginning to make minimalist works. [For] abstract monochrome works, we’re trying to have a kind of ulterior motif or just a different kind of subject matter. Because it just started as a painting of my friends’ skin colors and a kind of commentary on modernism, from the start it wasn’t so tilted towards racial issues. It was a little bit surprising to me at the time that it got read almost exclusively that way. So, I don’t know what that looks like in another country, especially in another country like Korea where race isn’t such a constant, pressing everyday issue. I suspect it looks like a very American kind of subject matter in Korea. Just because we’re living in it all the time, it’s like if you’re a fish swimming in the water, you don’t know they’re in the water even. There’re some works [at the 1993 Whitney Biennale] that were so overtly political that they probably did carry some of their political messages through to East Asia. But that particular work, Synecdoche, from that audience’s point of view, it probably aligned more closely with the content that I envisioned when I first made the piece.

Please tell us how your Bruise paintings came into being.

This is gonna sound implausible, and at least funny, but I didn’t realize that I was setting out to make skin paintings again when I started to make these series of paintings on bruising. The occasion for thinking about bruising was again, very different from what the audience eventually thought it was. My impetus for starting a series of paintings on the subject of bruising was after reading a passage from a poem by Carl Philips, called “Alba: Innocence”. The passage depicted a bruise on his lover’s body in a way that made me realise that this was a perfect subject matter for my work. Bruising is less much easy to look at it in neutral way. Yet in this poem, where I found the bruise as the subject matter, it’s look at as somewhat neutral and even beautiful in a way. It’s very aestheticised. So I think I was attracted to that, not because I want to paper over conflict and aestheticise everything but just it’s very interesting to me to have such a “hot” subject matter be presented in a “cool” way. I remember so clearly making these paintings during the campaign—the presidential campaign of 2016, and then the show opened literally right at the moment of his inauguration. There were all these horrible things happening in the States especially, but in the world too. There were lot of African Americans being killed by the police, just one after the other, so when these paintings were presented for the first time, it seemed very clear to the audience that the subject matter was about that kind of trauma.

When you walked into the studio, I said it’s a good thing I haven’t ruined this work. What I was implying is that when one uses so much dyeing, there’s so much possibility for something to happen that just doesn’t look right. For instance, like a hard edge line can happen, or you know, like a fold. It can just happen by mistake. That’s really hard to then make up for it. You can’t really paint it out. It’s a kind of a controlled randomness. Because essentially they’re stain paintings, the process of the staining is somewhat analogous to bruising. If you think about it, a bruise is just like a stain underneath the skin. It’s kind of a squeamish thing to say, but it’s kind of exactly what it is. I think in the end, color is in the mind. But, we get fooled into thinking that it’s in material or even in light, but it’s always, ultimately it’s always our mind—how it perceives light and material.

Previously, you mentioned that the rise of popular media makes it difficult for an artist to reside comfortably within the bubble of one’s studio. How much does this resistance against staying in the bubble affect your art practice?

I want my work to be in relation to the world ultimately. I don’t want to be an artist who holds himself up in his studio and makes something that’s just some figment of myself. On the other hand, I don’t want to make work that just reacts to whatever happens to be going on right at this moment. There’s a particular situation happening now, with the all these children who have been detained by the Trump administration. It’s just weighing very heavily on my conscience and [also for] a lot of people in this country. I mean it’s not like I’m actively resisting making work about that particular subject matter. I don’t think I would do that. On the other hand, it’s pervading my psyche at the moment, and it’s almost impossible for it not to affect me in some way. I distinctly remember answering a question about being a political artist and saying that when I shut the door to my studio, I just leave all that stuff outside. So I think I have moments of that, so it’s really hard to answer that question.

바이런 킴과의 인터뷰

2018년 7월 2일

뉴욕

1993년 휘트니 비엔날레에서 <제유법>을 전시했던 경험을 나눠주시겠어요?

<제유법>은 90년대 초 (아마도 80년대 말에)에 시작되었습니다. 제 캐나다인 친구가 놀러 왔을 때, 그냥 친구 이마 피부의 색을 가져다 칠했습니다. 당시 제가 막 미니멀리스트 작품을 만들기 시작했을 때였습니다. 단색 추상 작품들을 만들 때, 우리는 숨은 뜻이나 색다른 주제를 표현하려고 합니다. 그저 친구들의 피부 색을 칠한 그림이자 모더니즘에 대한 코멘터리 정도로 시작했기에, 작품이 애초부터 인종 문제에 치우쳐 있지는 않았습니다. 거의 인종 문제 관련으로만 해석된다는 점이 저에겐 솔직히 조금 놀라웠습니다. 그래서 특히 한국처럼 인종이 매일같이 언급되거나 급히 해결해야 할 문제가 아닌 나라에서 작품이 어떻게 읽힐지는 잘 모르겠습니다. 한국에서는 굉장히 미국적인 주제로 비춰질 것이라 생각됩니다. 항상 그런 상황들 속에 놓여 있다 보니, 헤엄치는 물고기가 자신이 물 속에 있는지조차 모르는 것처럼 자연스럽게 흘러가게 되죠. 1993년 휘트니 비엔날레에는 확연하게 정치적이라 그 메세지를 동아시아 널리 퍼뜨렸을 작품들이 있었습니다. 하지만 <제유법> 같은 경우에는, 아마 제가 맨 처음 작품을 만들었을 때 생각했었던 주제가 관객 입장에서는 좀 더 가까울 것입니다.

<멍 시리즈>를 어떻게 작업하게 되셨는지도 말씀해 주실 수 있을까요.

웃길 수도 있고, 믿기지도 않겠지만, 멍 시리즈를 작업하기 시작했을 때 또 피부에 관련된 그림을 그리고 있다는 걸 자각하지 못했습니다. 멍에 대한 제 관점은 또다시 관객들이 결론적으로 생각한 것과 매우 달랐습니다. 칼 필립스의 시 “알바: 순수”의 한 부분에서 자극을 받아 멍 시리즈를 시작하게 되었습니다. 애인의 몸에 남은 멍에 대한 작가의 묘사는 제 작업에 완벽히 걸맞는 주제였습니다. 멍은 중립적인 태도로 보기 훨씬 어려운 소재입니다. 하지만 제가 이 시에서 찾은 멍이라는 주제는, 어떻게 보면 중립적인 데다가 아름답기까지 합니다. 엄청나게 미화되었죠. 제가 그 주제에 끌렸던 이유는 갈등이나 충돌을 숨겨 모든 걸 미화시키려는 게 아니었습니다. 그저 그렇게 “뜨거운” 주제가 “차가운” 방식으로 표현되는 게 엄청나게 흥미롭기 때문이었죠. 2016년 대선 캠페인 당시에 이 작품들을 만들던 때가 아직도 생생합니다. 전시회는 (트럼프 대통령이) 정확히 취임하던 순간에 열렸습니다. 특히 미국에서 이런 끔찍한 일들이 많이 일어났지만, 이런 일들은 전세계적으로 벌어집니다. 당시에 많은 아프리카계 미국인들이 차례로 경찰에게 죽임당했기에, 작품이 처음 공개되었을 때 관객들은 그런 트라우마에 관한 내용임을 확신했습니다.

(큐레이터님이) 작업실로 들어오셨을 때, 제가 이 작품을 망치지 않은 게 다행이라고 했었죠. 제 말의 의도는, 염색을 너무 과하게 할 경우 결과물이 이상하게 나올 확률이 높다는 겁니다. 예를 들어, 모서리만 진하게 나타난다거나 접힌 것처럼 보일 수가 있습니다. 단순한 실수로 일어날 수 있는 일들이죠. 그 이후에 대처하기가 매우 어려워집니다. 칠해서 덮거나 지울 수는 없습니다. 통제된 무작위성 같은 거라서요. 작품이 근본적으로 스테인(얼룩, 착색) 페인팅이기 때문에, 착색되는 과정은 멍드는 것과 같은 맥락에 있습니다. 생각해 보면, 멍은 피부 아래에 있는 얼룩과도 같지요. 이렇게 말하면 메스꺼울 수도 있지만, 정확한 표현이 맞습니다. 결국 색은 마음에 있는 것이라고 생각합니다. 색이 소재나 빛에 있다고 속곤 하지만, 항상 궁극적으로는 우리의 마음 속에 존재합니다. 마음이 어떻게 빛이나 소재를 인지하는지에 따르는 것입니다.

이전에, 대중 매체의 성장이 예술가가 작업실에서만 편안히 작업하는 걸 방해한다고 말씀하셨습니다. 작업실에서만 지내는 걸 반대하는 이 현상이 작가님의 예술에 어떠한 영향을 미치나요?

저는 근본적으로 제 작업이 바깥 세상과 연관되길 바랍니다. 저는 스스로를 작업실에 가두고 자신의 상상력만 펼치는 작가가 되고 싶지 않습니다. 한편으로는, 지금 이 순간 일어나고 있는 일들에만 관련된 작품을 만들고 싶지도 않습니다. 지금 트럼프 정부에게 억류된 아이들과 함께 일어나고 있는 여러 상황들이 있습니다. 그저 제 양심에 무게를 두고 이 국가의 많은 사람들을 위하는 일입니다. 제가 그런 특정 주제에 관한 작업을 열성적으로 거절한다거나 하는 건 아닙니다. 제가 그러진 않으리라 생각해요. 다른 한 편으로는, 그런 상황들이 제 심리를 파고들다 보니 작품에 조금이라도 영향을 주지 않는 건 불가능합니다. 제가 정치적 예술가냐는 질문에 했던 대답을 똑똑히 기억납니다. 제가 작업실 문을 닫아버리면 바깥에 있는 것들은 신경을 쓰지 않는다고 했었죠. 제게 이런 순간들이 있다 보니까, 이 질문에 대답하기가 무척 어렵네요.